In the vast and intricate tapestry of Japanese mythology, few figures are as pivotal and resonant as Hikohohodemi no Mikoto. Known to many by his more popular name, Yamasachi-hiko, or “Luck of the Mountains,” he is a deity whose story forms a cornerstone of the divine lineage of Japan’s imperial family. His myth, rich with drama, magic, and profound symbolism, is more than just a tale of adventure; it’s an exploration of the delicate balance between land and sea, humanity and the divine, and the consequences of pride and patience. From a simple hunter to a serpent prince and the progenitor of an imperial dynasty, the journey of Hikohohodemi is a foundational narrative that continues to shape Japanese cultural and religious identity.

The Quarrel of the Brothers: Mountain vs. Sea

The story begins with two brothers, born of the great sun goddess Amaterasu’s descendants. The elder brother, Hoori no Mikoto, was known as Umisachi-hiko, or “Luck of the Sea,” a skilled fisherman who mastered the ocean’s bounty with his magical hook. The younger, Hikohohodemi no Mikoto, was the aforementioned Yamasachi-hiko, a hunter whose prowess lay in the forests and mountains, relying on his bow and arrows. Their lives were a study in contrast, one living by the rhythmic tides and the other by the quiet, steady pulse of the earth.

One day, Yamasachi-hiko, weary of his hunting, proposed a trade of their tools. Umisachi-hiko reluctantly agreed, and the brothers switched their trades. But as fate would have it, Yamasachi-hiko, inexperienced in the ways of the sea, lost his brother’s treasured fish hook. He fished for days without success, growing increasingly desperate. When he finally confessed the loss, Umisachi-hiko was furious, demanding his exact hook back and refusing to accept a thousand newly crafted ones in its place. Overwhelmed by despair and his brother’s unyielding anger, Yamasachi-hiko stood weeping on the shore, a classic hero in a state of hopeless paralysis.

The Descent to the Dragon Palace

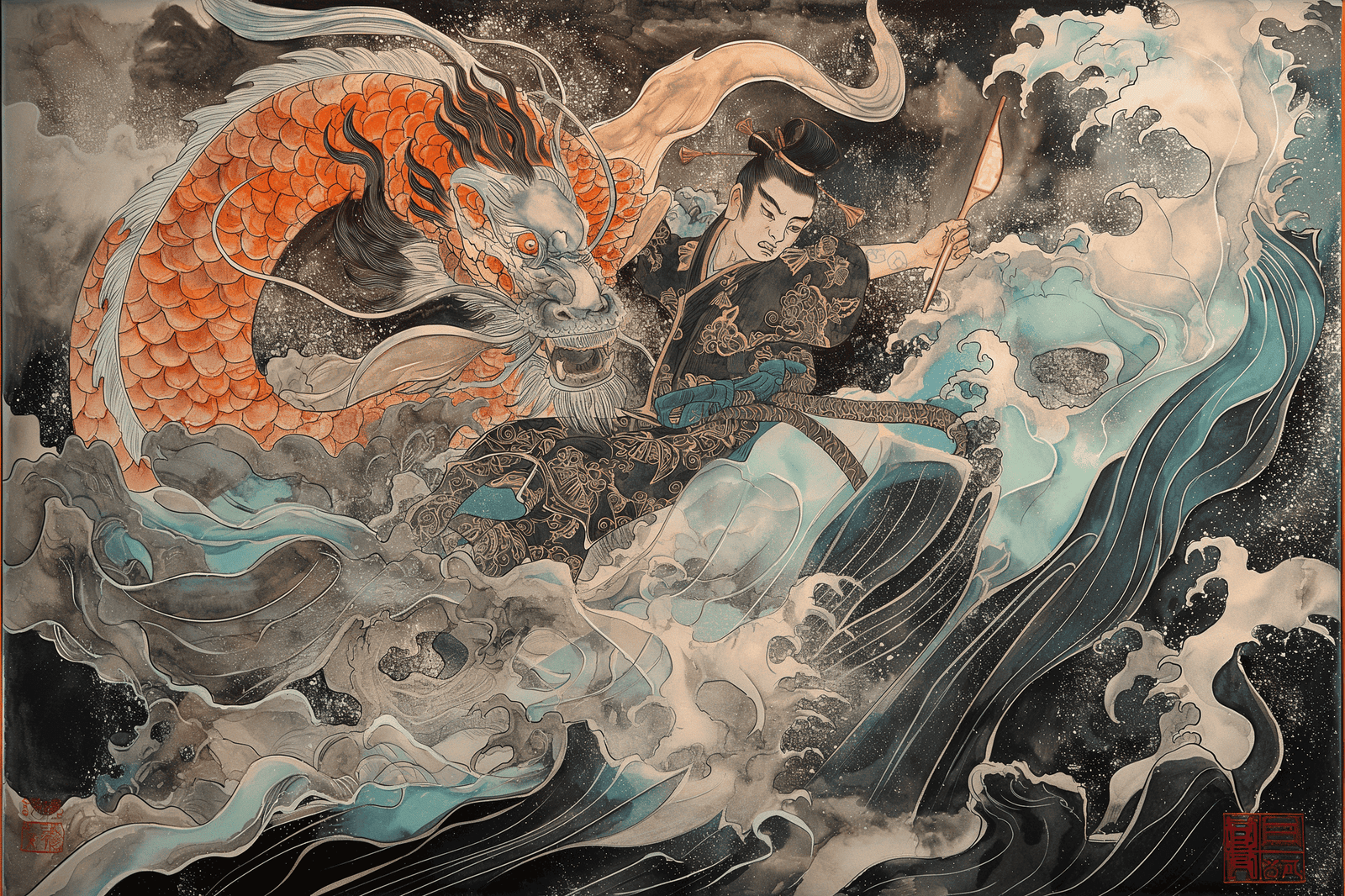

It was in this moment of vulnerability that a divine guide, Shiotsuchi-no-Kami (the Old Man of the Tides), appeared before him. Taking pity on the grieving prince, he advised Yamasachi-hiko to travel to the bottom of the sea. He built a small, basket-like boat and instructed Yamasachi-hiko to ride the waves until he reached the magnificent Ryūgū-jō, the underwater palace of the great Sea God, Ryūjin.

Upon his arrival, Yamasachi-hiko was immediately captivated by the splendor of the palace, built of shimmering coral and pearl. He was met by the Sea God’s beautiful daughter, Toyotama-hime, or “Princess Abundant Jewel.” She instantly fell in love with him, and their love story began to unfold. Yamasachi-hiko, in turn, was so enchanted by the princess and the idyllic life in the palace that he completely forgot the reason for his journey. For three years, he lived in blissful harmony, lost in the wonders of the undersea world.

However, the longing for home eventually returned. He confessed his plight to Toyotama-hime, revealing the loss of his brother’s hook. Her father, Ryūjin, sympathetic to the young prince’s predicament, summoned his sea creatures and ordered them to search for the hook. The search was fruitful: they discovered the hook had been swallowed by a fish. The Sea God retrieved it and presented it to Yamasachi-hiko, but not without imparting some critical advice. He gave his son-in-law two magical jewels: the Shiomitsu-tama (Tide-Ebbing Jewel) and the Shiohiru-tama (Tide-Flowing Jewel). He instructed Yamasachi-hiko to use them to control the tides and teach his brother a lesson in humility.

The Return and the Birth of a Dynasty

Armed with the hook and the jewels, Hikohohodemi no Mikoto returned to the surface. He found his brother, Umisachi-hiko, still angry and unforgiving. He returned the hook, but Umisachi-hiko’s resentment lingered. At this point, Yamasachi-hiko used the magical jewels. He first used the Tide-Ebbing Jewel, which caused the tide to recede so far that Umisachi-hiko’s fishing grounds became barren. When the furious brother threatened him, Yamasachi-hiko used the Tide-Flowing Jewel, causing the tides to surge and nearly drown him. The power of the sea was now in his hands, and Umisachi-hiko was finally humbled. He bowed his head in defeat, pledging his loyalty and service to his younger brother and his descendants forever. This act symbolically established the dominance of the lineage of Yamasachi-hiko, a figure of terrestrial wisdom and cosmic order, over the fickle, turbulent sea.

Soon after, Princess Toyotama-hime came to the land to give birth to their child. As she went into labor, she told her husband not to look at her during the birth, as she would be in her “true form.” But consumed by curiosity, Yamasachi-hiko peeked into the hut. To his horror, he saw his beautiful wife in the form of a massive sea serpent, her form twisting and writhing in agony. Ashamed and heartbroken that her secret had been revealed, she abandoned the child and returned to the sea, sealing the separation between the divine realms of land and water. The child, Ugaya-fukiaezu no Mikoto, was raised by her sister, Tamayori-hime. This son would go on to be the father of Emperor Jimmu, Japan’s first emperor, forging a direct and sacred link between the divine and the imperial line.

Symbolism and Legacy

Hikohohodemi no Mikoto’s myth is steeped in profound symbolism. He represents a bridge between the realms: a deity who, though a master of the mountains, finds love and power in the depths of the sea. His journey from an ordinary hunter to a divine prince reflects a spiritual evolution, where humility and wisdom triumph over arrogance. As a Kami, he is revered as a protector of hunters and fishermen and a bringer of good fortune, often associated with agricultural bounty and the control of natural forces. His story is particularly significant for its role in solidifying the divine legitimacy of the Japanese imperial lineage. The myth explains that the emperors of Japan are not merely human rulers but direct descendants of the kami, linking the nation’s leadership to the very gods who shaped the world.

Today, Hikohohodemi no Mikoto is venerated at shrines across Japan, most notably Kirishima-Jingū, where he is celebrated for his role in uniting the earthly and aquatic domains. His tale serves as a timeless reminder of the interconnectedness of all things, the power of humility, and the extraordinary origins that lie at the heart of Japanese identity. The story of the hunter who became a serpent prince is not just an ancient legend; it is a living myth that continues to resonate with the soul of a nation.