The spiritual pantheon of Japan is rich with an infinity of deities, the Kami, but it is also populated by a multitude of strange and fascinating creatures: the Yōkai. These supernatural beings, ranging from simple trickster spirits to formidable demons, embody the mysteries, fears, and uncontrolled forces of nature. Among them, the Tengu (天狗, literally “Heavenly Dog”) occupies a unique and complex position. Neither purely Kami nor simply a demon, the Tengu is a transitional figure, a powerful mountain spirit whose history and legends reveal the dynamic spiritual interactions between Shintoism, Buddhism, and Japanese ascetic practices.

The Tengu’s evolution, from a pernicious demon to a dreaded and respected guardian, makes it an ideal subject for exploring the fluidity between the sacred and the profane in Japanese culture.

I. Complex Origins: From Chinese Celestial Phenomenon to Japanese Bird Demon

The very name of the Tengu, written with the characters for “Heaven” (天, Ten) and “Dog” (狗, Gu), originates from a creature in Chinese folklore, the Tiāngǒu, a canine demon often associated with eclipses and meteors. However, in Japan, the figure transformed radically, shedding its canine form to adopt avian characteristics.

The Kotengu: The Original Form

The earliest Japanese mentions of the Tengu, dating back to the 8th century (Nara Period), depict it as a malevolent being, often identified as a large bird of prey, such as a kite or a crow. These creatures are called Karasu Tengu (烏天狗, Crow-Tengu) or Kotengu (小天狗, Small Tengu). They were feared for their demonic actions:

- Kidnappings: They captured monks and children, leading them astray in the sacred mountain forests to drive them insane.

- Destruction: They were accused of causing fires, storms, and disasters, acting as disruptors of the Buddhist order.

- Vanity: They were considered spirits of arrogance, symbolizing the spiritual consequences of the sin of pride.

During this era, the Tengu was a demon in the strict sense, an agent of chaos that opposed Buddhist doctrine by tempting or tormenting ascetics.

The Daitengu: The Humanoid Transformation

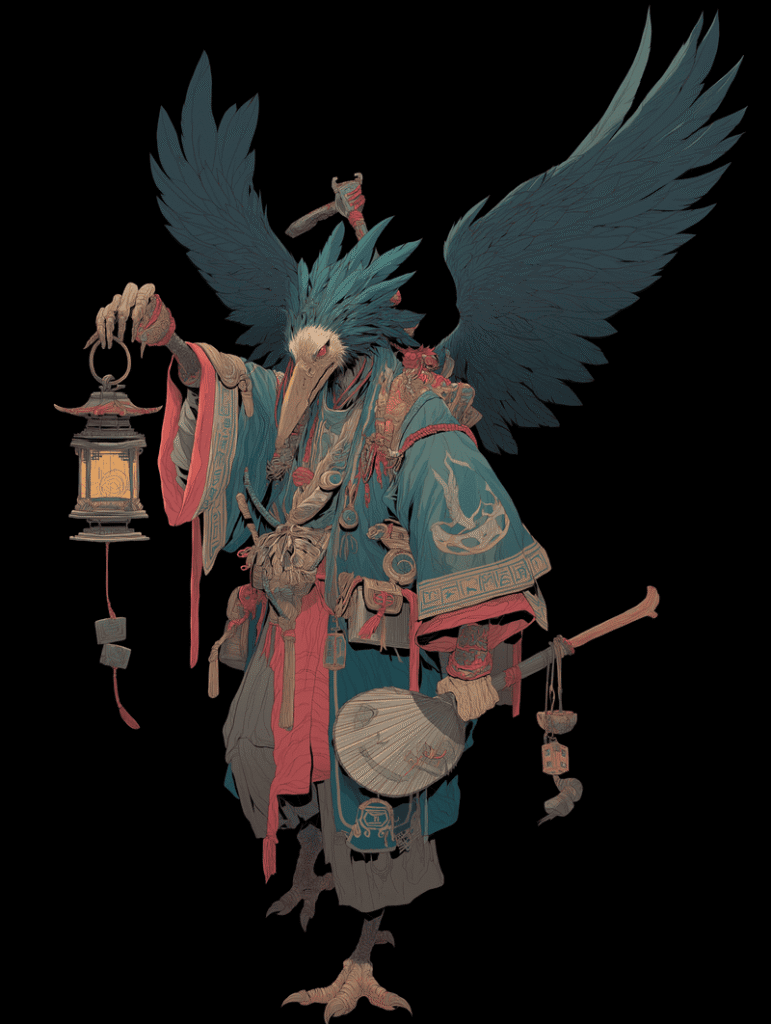

Over time, during the medieval period (12th-16th centuries), the Tengu’s image evolved into its most famous form: the Daitengu (大天狗, Great Tengu). These creatures have a more humanoid appearance, characterized by:

- The Long Nose (or Hanatengu): This prominent, often bright red nose is an anthropomorphization of the original beak of the Crow-Tengu and has become the creature’s defining feature. It also symbolizes arrogance and pride, as the Japanese expression tengu ni naru (“to become a Tengu”) means “to get a big head” or “to become conceited.”

- The Yamabushi Attire: The Daitengu is generally dressed like a yamabushi (mountain ascetic practicing Shugendō), wearing the distinctive robe, small black cowl, and tokin (headwear).

- Wings and the Ha-Uchiwa: The wings remain, a testament to its avian origins, and it often holds a ha-uchiwa, a feathered fan. This fan is a symbol of its power over the winds, allowing it to create gusts or control weather phenomena.

The Tengu transitioned from a malevolent bird to a semi-human, semi-divine being, reflecting the mysteries and esoteric practices of Shugendō that took place in the mountains.

II. The Tengu and Shugendō: Master of Sacred Mountains

The Tengu’s deepest relationship is not with a specific Kami, but with the very concept of the sacred mountain and the practice of Shugendō (the “Way of Power through Experience”).

The Mountain: A Place Between Two Worlds

In Shintoism, the mountain is traditionally a sacred place (yama no Kami), the domain of spirits and ancestors, the meeting point between heaven and earth. For Shugendō, a syncretic blend of Shintoism, Esoteric Buddhism (Mikkyō), and shamanism, mountains are harsh training grounds where ascetics (yamabushi) seek to acquire spiritual powers.

The Tengu is the guardian, the tutelary spirit of these mountains. Its yamabushi appearance is a recognition that these creatures embody the untamed power of the mountain, a power that ascetics seek to master or appease. They are often seen as yamabushi who succumbed to arrogance and were banished to the realm of non-redemption, symbolizing the failure of the spiritual quest.

The Feared Teacher

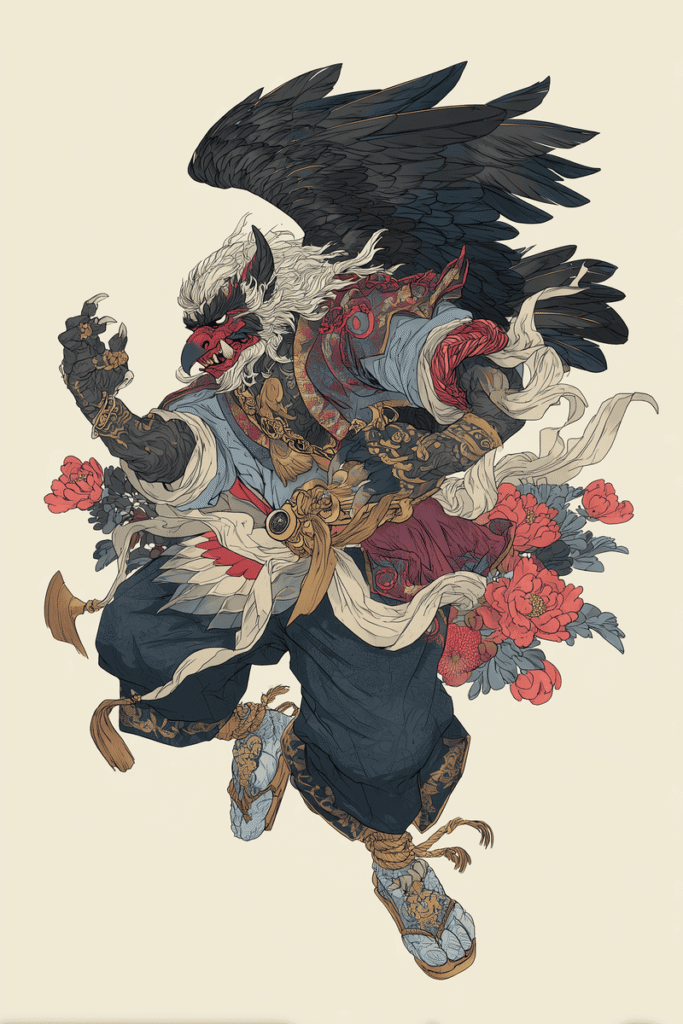

Over the centuries, the Tengu acquired the function of a mentor and a master of martial arts and military strategies. The most famous of the Daitengu is Sōjōbō (the Tengu of Mount Kurama, near Kyoto), often nicknamed the “King of the Tengu.”

The most famous legend concerning him recounts that he trained the young orphan Minamoto no Yoshitsune (then known as Ushiwakamaru) in the art of the sword (kenjutsu) and military tactics. Thanks to Sōjōbō’s supernatural instruction, Yoshitsune became a legendary warrior. This legend illustrates a fundamental change: the Tengu, once solely malevolent, becomes a source of power and esoteric knowledge, although still outside established social and religious norms.

III. The Tengu at the Border of Shintoism and Buddhism

The Tengu’s complexity lies in its ambiguous position between the two great Japanese spiritual traditions:

A Buddhist Antagonist

Buddhism long viewed the Tengu as an obstacle to enlightenment. Buddhist legends depict it as the spirit of arrogant or vain monks who, due to their spiritual pride, could not attain Nirvana. They are thus banished to eternally wander the mountain realm, the Tengu-dō (the Way of the Tengu), a kind of sixth realm of existence in Buddhist cosmology. It is the personification of the sin of pride that corrupts the hearts of ascetics.

A Minor Shinto Kami

In the Shinto tradition, the Tengu is often revered as a minor Kami, particularly in mountain shrines. It is honored as a Protector Kami (Gozon), capable of warding off evil spirits, protecting forests, and ensuring good harvests, especially after its evolution into a less capricious figure.

A notable association is with Saruta-hiko Ōkami, an important Shinto Kami. Saruta-hiko is a divine earthly chief, known for his very long nose, which naturally led to a syncretism or identification with the long-nosed Daitengu. Saruta-hiko is the chief of the Kuni-Kami (earthly deities) and is often honored as a Kami of crossroads and guidance. This connection elevates the Tengu’s status, integrating it into the Shinto pantheon of natural forces.

IV. Cultural Impact and Contemporary Symbolism

The Tengu’s legacy is ubiquitous in Japanese culture, traversing eras and media:

Masks and Festivals

Tengu masks, recognizable by their exaggeratedly long nose and red face, are commonly sold as good-luck charms to ward off evil or are worn during Matsuri (Shinto festivals) in mountainous regions. They serve as powerful symbols of protection and the raw energy of the mountain.

Ethics and Morality

Even in modern language, the expression tengu ni naru serves as a warning against arrogance, a concept that remains morally central in Japanese society.

Pop Culture

The Tengu is a recurring figure in manga, anime, video games, and cinema. It is often portrayed as a lonely war master, a winged warrior, or a powerful but secretive being who lives in seclusion, preserving lost knowledge or techniques. These contemporary representations exploit its duality: the wisdom and power inherited from the mountains, tempered by the threat of anger and pride.

In conclusion, the Tengu is much more than a simple Yōkai; it is a mirror reflecting Japanese beliefs about the nature of spiritual power. It embodies the danger and majesty of the mountain, the historical conflict between Buddhism and native cults, and the spiritual consequence of human vanity. At once a celestial messenger (its name), a corrupting demon (its earliest form), and a wise guardian of the mountains (its final form), the Tengu is living proof of the dynamic complexity of the Japanese spiritual cosmos, where the boundaries between the Kami and the Yōkai remain, like the mountain paths it traverses, forever mysterious and sometimes dangerous.